Por Judy Maltz

Traducido por Marc Schnitzer de un artículo publicado en la edición inglesa de Haaretz.

Publicado a las 13:48

En una típica mañana de Shabat en estos tiempos no tan típicos, el rabino Roberto Graetz abre su servicio semanal de oración por Zoom a las 8 a.m. Son las 8 a.m. Hora del Pacífico, ya que Graetz no se encuentra en Puerto Rico, donde normalmente estaría en esta época del año, sino en el estudio de su hogar permanente en Lafayette, California.

En San Juan, donde se encuentra físicamente su congregación, el reloj acaba de dar las 11 a.m. Y en Argentina, Brasil y Chile, donde residen los rabinos en formación que lo ayudan a dirigir los servicios, ya es mediodía, es decir, dos horas antes que Guatemala, donde su cantora, su guitarra ya posada en su regazo, ansiosa, espera su señal para empezar.

Encontrar el momento óptimo para celebrar los servicios matutinos de Shabat, dice el rabino reformista nacido en Argentina, puede ser un desafío cuando su congregación está a casi 4,000 millas (casi 6,500 kilómetros) y varias zonas horarias de distancia. No facilita las cosas que algunos de los que comparten las responsabilidades semanales con él estén aún más lejos.

“Ahora que cambiaron los relojes aquí en la costa oeste, mis feligreses me pidieron que comenzara a las 7 a.m. mi tiempo ”, dice en una llamada telefónica desde su casa en California. “Les dije que hay límites en cuanto a qué tan temprano estoy dispuesto a despertarme, y que tendrían que continuar sin mí en los próximos meses hasta que volvamos a la hora normal”.

Nueva oportunidad de vida

La pandemia de coronavirus ha obligado a las sinagogas de todo el mundo a adaptarse e improvisar para mantener a sus feligreses comprometidos y mantenerse pertinentes mientras se cumplen los requisitos de distanciamiento social. Para las congregaciones reformistas, que no están sujetas a restricciones halájicas sobre el uso de la electricidad, plataformas como Zoom han hecho posible que se sigan celebrando los servicios de Shabat y festivos de forma remota.

Sin embargo, el Temple Beth Shalom en San Juan es el caso poco común de una congregación que no solo ha mantenido una apariencia de normalidad durante esta crisis, sino que incluso ha encontrado la oportunidad de extenderse más allá de sus fronteras.

“Lo que hemos estado experimentando aquí en las mañanas de Shabat durante los últimos meses es simplemente asombroso”, dice Shula Feldkran, nacida en Israel, quien se mudó a Puerto Rico hace más de 50 años y ha sido durante mucho tiempo miembro activo de Beth Shalom.

“Dada la opción, la mayoría de la gente obviamente preferiría estar en una sinagoga real. Pero para mí, debido a que tengo un poco de sordera, los servicios de Zoom son aún mejores ”, dice la señora de 75 años, bromeando a medias.

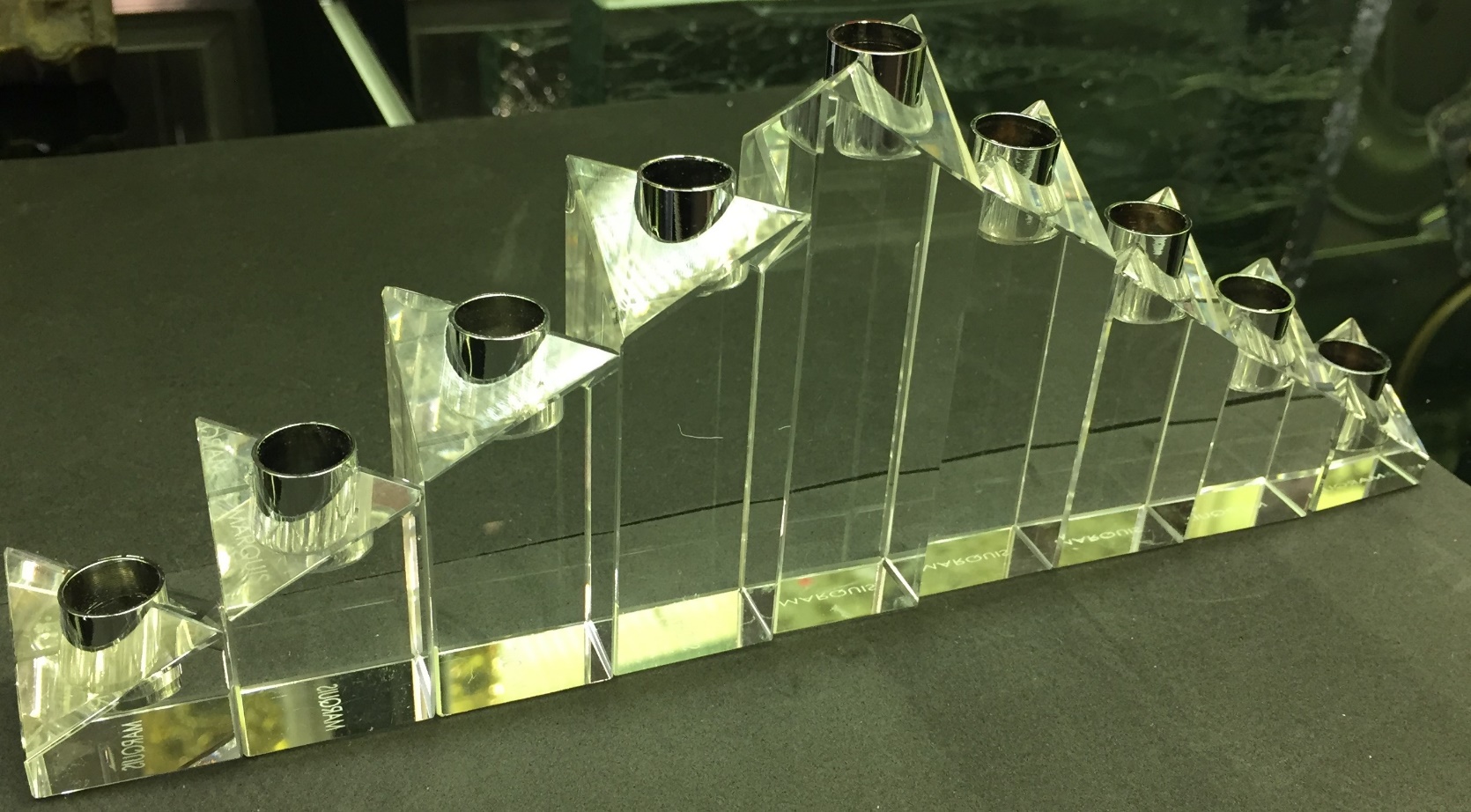

Beth Shalom, la única congregación reformista en Puerto Rico, fue fundada en el 1967 por judíos norteamericanos que habían comenzado a mudarse a la isla en busca de oportunidades comerciales. Debido a las disparidades lingüísticas y culturales, no se sentían cómodos ni bienvenidos en la congregación conservadora ya establecida, fundada por judíos que habían huido de Cuba después de que Fidel Castro subiera al poder, por lo que comenzaron su propio lugar de culto.

La mayoría de los hijos de estos judíos de América del Norte finalmente abandonaron Puerto Rico, y solo quedan unos pocos miembros de la generación fundadora de Beth Shalom, la mayoría habiendo muerto o regresado al continente por motivos de salud.

La congregación recibió una nueva y bastante inesperada oportunidad de vida en los últimos años gracias al creciente número de puertorriqueños que han descubierto el judaísmo, algunos de ellos con ascendencia judía, y se están convirtiendo. Hoy en día, los judíos por elección representan más del 90 por ciento de la membresía paga en Beth Shalom.

La congregación ha dependido durante mucho tiempo de rabinos “voluntarios”, por lo general, rabinos jubilados de América del Norte, que pasan algunos meses en la isla. Los servicios de los viernes por la noche se llevan a cabo en inglés, para beneficio de los fundadores restantes y los “pájaros de nieve” [norteamericanos que pasan el invierno en Puerto Rico] , y en la mañana de Shabat en español. Según Graetz, en tiempos previos al coronavirus, los servicios de los viernes por la noche atraían a un promedio de 15 a 20 participantes, mientras que los servicios matutinos de Shabat atraían entre 40 y 50.

Desde que los servicios se pusieron en línea a mediados de marzo después de que el coronavirus azotara a Puerto Rico, las cifras han aumentado constantemente, dice Graetz. Señala que en las últimas semanas, entre 80 y 90 fieles han estado asistiendo al Zoom del sábado por la mañana.

Cuando la pandemia de coronavirus golpeó a Puerto Rico, el rabino que normalmente se ofrece como voluntario durante los meses de invierno acababa de regresar al continente, y los miembros de Beth Shalom se quedaron sin un rabino y sin un lugar para rezar, ya que su sinagoga, como todos los lugares de culto, habían sido ordenados cerrados. “Me ofrecí a ejecutar los servicios matutinos de Shabat de forma remota, y otro colega mío se hizo responsable de los servicios del viernes por la noche”, relata Graetz, de 74 años. “En algún momento me cansé un poco, así que me acerqué a tres de los estudiantes del nuevo centro de formación rabínica en Argentina donde enseño, y les pregunté si les gustaría hacerse cargo, ya que había poco trabajo congregacional real que pudieran hacer en estos días. Les dije que yo los capacitaría y los guiaría, y dijeron que estarían encantados.”

Esta es una segunda carrera para los tres estudiantes rabínicos, dice. Edy Huberman, de Buenos Aires, es director ejecutivo de la Fundación Judaica de Argentina (una asociación de sinagogas progresistas); Martín Hirsch, de Concepción, Chile, es profesor de ingeniería; y Pablo Schejtman, un argentino radicado en Fortaleza, Brasil, es ejecutivo de seguros.

Por lo general, Graetz se habría ido para su período anual en Puerto Rico justo antes de los Iamim Noraim, así que cuando llegó septiembre y todavía estaba atrapado en casa, llamó a sus estudiantes y les hizo una oferta. “Dije: hagamos esto juntos”.

Durante Rosh Hashaná, se les unió en sus servicios en línea Adat Israel, una comunidad judía reformista en Guatemala cuyos miembros son todos conversos. Rebecca Orantes, una aspirante a rabina con una hermosa voz, fue inmediatamente reclutada como solista cantorial. *

‘Como presenciar una disputa talmúdica’

Una vez que se abrieron los servicios para los participantes fuera de Puerto Rico, los estudiantes rabínicos de Graetz preguntaron si también podían invitar a miembros de varias pequeñas comunidades judías que conocían en rincones remotos de Argentina y Chile. Graetz estuvo más que feliz de complacerlo. Mientras tanto, algunos de los “pájaros de nieve” regulares, atrapados en casa en el continente, habían comenzado a unirse.

Salatiel Corcos, un contratista de obras de 32 años que es el actual presidente de Beth Shalom, ve una tendencia con un gran potencial. “Ahora estamos empezando a pensar en cómo podemos atraer a otras pequeñas comunidades de habla hispana, comunidades que no tienen sus propios rabinos y no tienen su propio lugar para orar”.

Beth Shalom ya se ha acercado a una pequeña comunidad reformista en México, dice, y espera incorporarla pronto.

Para prepararse para el servicio de una hora y media, Graetz y sus tres estudiantes se reúnen en línea los jueves y dividen las lecturas. Graetz entrega el d’var Torá que se refiere a la lectura de la Torá de la semana, y sus alumnos se turnan para comentarlo. “A veces, es casi como presenciar una disputa talmúdica”, dice Marc Schnitzer, nacido en Estados Unidos, ex presidente de la congregación y profesor retirado de lingüística que lleva viviendo en la isla casi 45 años.

Después de la lectura de la Torá, los rabinos en formación recitan textos judíos, prosa y poesía pertinentes a la lectura semanal. “Esta es mi parte favorita de estos servicios”, dice Feldkran. “Aprendo mucho de eso”.

En las últimas semanas, se han aliviado las restricciones relacionadas con el coronavirus en Guatemala y se ha permitido que los miembros de la congregación local regresen a su sinagoga en cantidades limitadas. Graetz cuenta que era la primera vez en meses que los participantes en el servicio semanal de Zoom había visto un rollo de la Torá. “Todos vimos en línea mientras se sacaba la Torá del arca en la sinagoga de Guatemala, y debo decir que fue una escena muy conmovedora”, recuerda.

Las desventajas de asistir a los servicios en línea superan con creces las ventajas, dice Schnitzer. Pero eso no significa que el nuevo formato no tenga sus ventajas. “Por un lado, nuestros pájaros de nieve pueden sintonizar dondequiera que estén, así que ha sido muy agradable”, dice. “Para mí, personalmente, ha habido otro beneficio. Por lo general, mi esposa y yo íbamos a los servicios del viernes por la noche o del sábado por la mañana. Desde que comenzó la pandemia y los servicios se han movido en línea, asistimos a ambos. Así que se podría decir que ahora somos más activos en la congregación de lo que solíamos ser”.

Cuando la vida vuelva a la normalidad, Graetz confía en que sus feligreses en Puerto Rico elegirán lo real en lugar de Zoom. “Pero lo que hemos descubierto es que hay personas en comunidades aisladas de América del Sur que están hambrientas por este tipo de conexión, y no van a querer renunciar a ella “, dice. “Así que creo que habrá una comunidad virtual que seguirá existiendo incluso cuando esto termine”.

*Corrección: Adat Israel y el Templo Beth Shalom han tenido servicios de Shabat por Zoom en conjunto desde comienzos del verano, durante los cuales la tarea cantorial se ha alternado entre la soprano Evelyn Vazquez Díaz, del Templo Beth Shalom, acompañada de su esposo Angel Rojas, y Rebecca Orantes de Adat Israel. Sin embargo, tuvieron servicios independientes para los Iamim Noraim, incluyendo el servicio de Rosh Hashaná mencionado, durante los cuales la tarea cantorial para el Templo Beth Shalom fue provista por Evelyn y Angel, tal como han hecho por varios años. El Templo Beth Shalom agradece enormemente su dedicación y compromiso con la congregación. Regresar