It’s Almost Time for Hanukkah!

Text and display by Naomi Patz – Hanukkah 5781

Another name for Hanukkah is JAG URIM, the festival of lights. In the darkest season of the year, virtually every religious tradition includes symbols and ceremonies to offset fears and counter the unnerving absence of light. Obviously, this has been a much less significant feature of the season since the advent of electricity. Yet this year, the gloom and fear associated with the Covid-19 pandemic bring us back again to an atavistic sense of insecurity.

So, being cautious, wearing masks and keeping our distance, let us

CELEBRATE LIGHT!

The following are photographs of the menorot (aka hanukkiyot) and associated objects for the festival of HANUKKAH now on display in the museum case of Temple Sholom of West Essex, Rabbi Patz’s congregation in New Jersey, which Naomi curates.

The opening picture is an overview of the entire case. Each element (more or less) will follow.

Here goes:

OIL LAMPS

The story of the little cruse of oil, just enough for a single night, which last “miraculously” for eight nights, is the traditional reason given for the celebration of Hanukkah.

The real story is much more complex and involves the political realities that followed the victory of the Maccabees. It’s a fascinating story you should check out, if you don’t know it already. Apart from everything else, it demonstrates powerfully why this is an observance for adults, not just a fairytale with presents for the kids.

ANCIENT:

Oil lamps are what people used for light. The first slide shows five oil lamps (and a photograph of four others) from ancient Israel. All but one are replicas.

MEDIEVAL:

Although candles were first invented some 500 years before the Common Era, as late as the Middle Ages candles were mostly reserved for church ceremonies because they were very expensive. Only the wealthy could afford to burn them in their homes. Almost everyone used oil for lighting; the size, style and efficiency of the lamps determined the amount of light they cast. For most of the history of the observance of Hanukkah, our people used oil to mark the nights of the holiday.

The beautifully designed hanukkiyot in the next two slides (different views of the same objects, some reflected in the mirrored glass back of the case) are replicas of bronze menorot from medieval France and Italy. Their styles are reminiscent of Gothic and Muslim architecture. See the rose window in the triangular menorah in the lower left and the arches on the two replicas behind it.

The little cups at the front were filled with oil, and a small wick then laid on top to be lit from the pointed tip.

MODERN:

There are an incredible number of modern hanukkiyot, ranging from elegant and evocative to whimsical and totally kitschy.

Here is a small sample of the range:

A wooden menorah, painted on both sides with scenes from the story of Noah, the flood and the ark, by the contemporary Israeli artist, Yair Emanuel, a gift from our dear friends Sue and Jimmy Klau (z”l). As we discovered to our horror with the first version of this hanukkiyah we lit, the candles cannot be allowed to burn down by themselves. We have replaced it. Enough said.

This hanukkiyah is a replica of 18th century Dutch menorah featuring hearts and flowering vines, traditional motifs of Dutch Jewish art. Holders for wax candles have been placed into the traditional oil cups (which, on close observation, you will see are just for show).It is amazing how bright the illumination when all of the candles are lit!

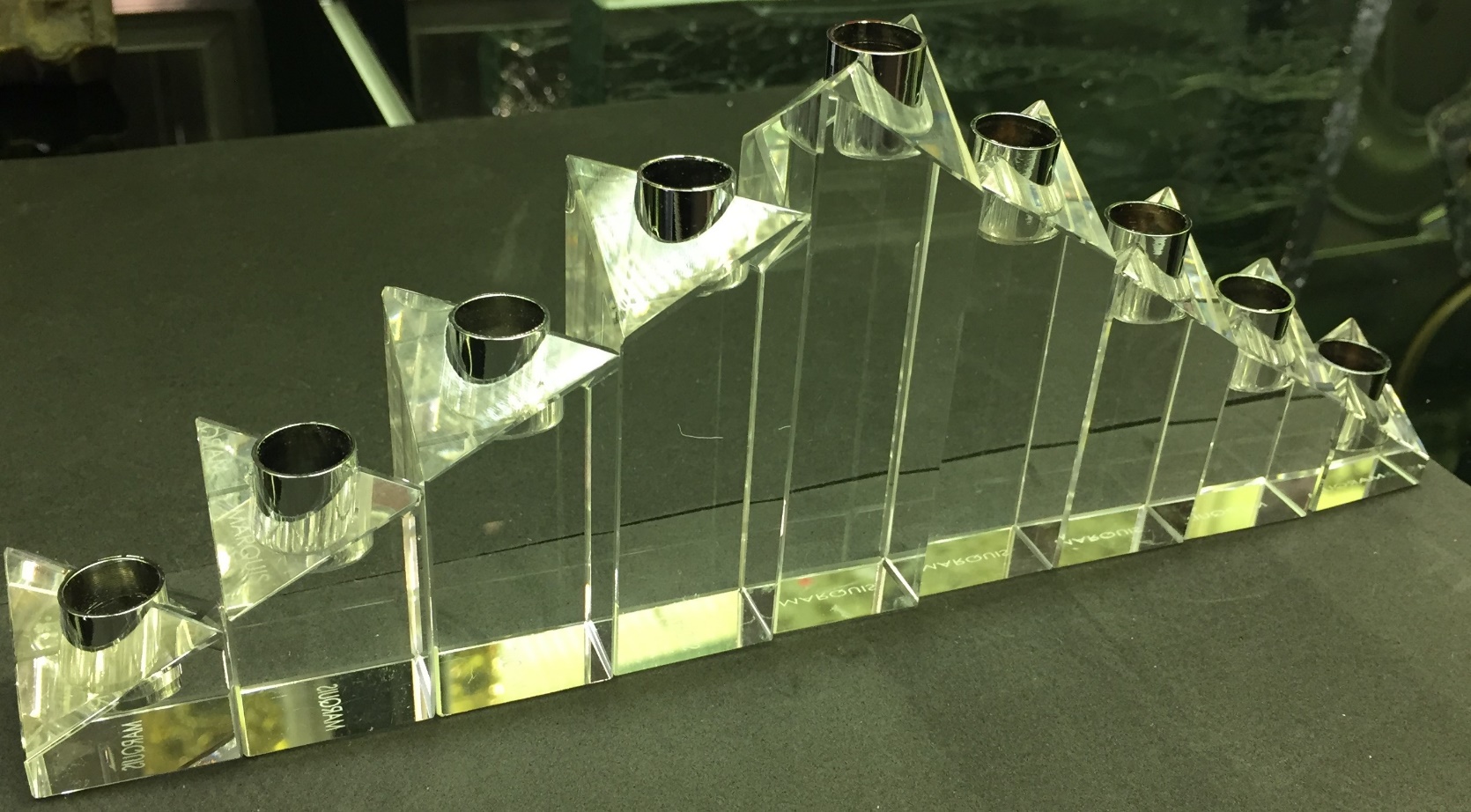

This hanukkiyah is Waterford Marquis crystal, the name unfortunately visible on the bottom of each of its nine pieces – one for each night’s candle and the tallest for the shamash, the “helper candle” that is used to light them all. It is designed to be displayed in a triangular shape, as here, or even random, so long as the shamash retains its function.

Please note that in traditional hanukkiyot, all eight candles or oil cups are always at the same height although the height of the shamash may differ. Note too that the candles are placed in the menorah from right (on the first night) to left (when all eight are burning) and lit starting with the newest light (in other words, from left to right).

This heavy glass modern hanukkiyah displays the eight candles at roughly the traditional level with the shamash set to the side. It is an oddly evocative piece designed to look like a block of water in motion.

Called the Wave Menorah by its creators, Joel and Candace Bless, it is made in a unique method the artists have dubbed “drip casting” to describe the hand cast hot glass in this menorah.

DREIDLS!

Dreidl (or dreidel) is the Yiddish name for the spinning “tops” designed hundreds of years ago in Yiddish-speaking communities in Europe to entertain children (and adults) during the eight nights of Hanukkah. The Hebrew word for dreidl is sevivon.

Gambling traditions associated with dreidls use hanukkah gelt (the coins that were the original gifts given on the festival) or walnuts as the “pot.” Every dreidl has a Hebrew letter on each surface: nun – standing for the word nes, miracle; gimel, for gadol, great; hey, for the word hayah, happened, or was; shin, for sham – there: A Great Miracle Happened There. (In modern Israel, the shin is replaced with the letter pey – for po = here.) Monetary (or walnut) values are assigned to each letter. Every player spins in turn. If the dreidl lands on nun, you get nothing (nichts). Gimel = ganz, winner take all! Hey gives the spinner halb, half of the pot, and poor you, if your dreidl stops on shin because it means you have to schenk your holdings into the pot.

The dreidls here are a wide variety ranging from a Waterford crystal to enameled tops to the Yaakov Greenvurcel six-sided metal in the lower right of the picture – and on to the wind-up little dreidl man behind it.

And now, another hanukkiyah.

This is a modern Israel ceramic piece depicting the stylized side of a Moorish building with an archway, peaked roof and lavish floral motifs. Although it can theoretically be lit with wicks in oil (we’ve tried), it works best – and looks terrific – with (ideally color-coordinated) candles creating a third dimension for the design.

Be sure to note the bird on the branch.

The artist is Shulamit.

The final three (top shelf) are contemporary plates for latkes (potato pancakes) or sufganiot (jelly doughnuts) or other “delicacies” of the festival, all of which rely on copious amounts of cooking oil in acknowledgement and celebration of Hanukkah.

The nursery school plate below was made many years ago when our New Jersey congregation had a gan yeladim, a 5-day a week nursery school. We recognize a menorah in the center, dreidls on either side, perhaps a match in turquoise (?), two Jewish stars (one much more recognizable than the other), and an unidentifiable purple object at the bottom. The artist (our younger daughter, Aviva) has no idea what that was meant to be.

The last plate, in the shape of a dreidl, shows the letter shin and part of the letter nun. Provenance: Probably made in China, it was purchased it at Marshalls.

The Talmud instructs us to “publicize the miracle” by displaying the Hanukkah lights in a window where it can be seen by passersby. Electric menorot enable moderns to observe this command safely – and to leave the lights burning, adding a new one each night, for the full week+ of Hanukkah.

JAG URIM SAMEAJ!!