Past, Present And Future

Past, Present And Future

Shabbat Nahamu 5781/2021

Rabbi Norman Patz

Temple Beth Shalom

I would like to share with you a brief look at our past, our present and our future in terms of Judaic tradition and Jewish persistence.

Shabbat Nahamu, the Sabbath of consolation, follows Tisha B’Av, the day which commemorates Jewish national tragedies in 586 BCE, 70 CE, and 1492 among others. On Tisha B’Av, Sefardic Jews have a kinah, a lament, that starts Ma nish’tana – “Why is this day different” (the same phrase in the Passover Haggadah that introduces the Four Questions). The kinah concludes with an expression of comfort and hope in the form of a poem written by the greatest of our medieval Jewish poets, Yehudah HaLevi. It is one of his shirei tziyon – songs of Zion.

Zion, don’t you have any response

to your last remaining flocks, your captive hearts,

who send you messages of love?

…

When I dream of how your exiles will return,

I become a harp (singing) your songs.

Our Jewish tradition assigns haftarot of consolation for the seven Shabbatot following Tisha B’Av. According to Rabbi David Abudraham, a great scholar who lived in 14th century Spain (hibur peirush ha-b’rakhot v’ha-tefilot – “A Composition Explaining the Blessings and the Prayers” – published in nine editions because of its popularity). The seven haftarot, all from Second Isaiah, provide an escalating drama of comfort and consolation that we can relate to. They make sense in terms of our modern understanding of the psychology of grieving.

The first week’s haftarah, (Isaiah 40:1-26), “seek comfort My people,” describes a people who struggle to be reconciled with God. The second haftarah (Isaiah 49:14-51:3), laments that “God has forsaken us.” The third (Isaiah 59:11-55:5), describes Israel as nevertheless still stubbornly seeking comfort from God. In the fourth week’s haftarah (Isaiah 51:12-52:12), we read God’s response: “I, I alone will comfort you.”

And so, in the fifth and sixth weeks, we have new reaffirmations of Israel’s faith in God. The haftarah for the fifth week (Isaiah 54:1-10), “Sing O barren one, you who bore no children… break out, sing aloud!”

And in sixth week (Isaiah 60:1-22), “Arise, shine for your light has dawned.” And finally, in week seven (Isaiah 61:10-63:9), “I will rejoice … Redemption is on the horizon.”

Abudraham portrays the progression of haftarot as going from despair to renewed faith and exultation. That’s the way our tradition has treated the devastating impact on our people’s continuing existence. And all of this, of course, in the words of Jews living in exile from Israel, the still-yearned for ancestral homeland.

Fast forward to the present. Israel has been realized. The ingathering of the exiles has begun. The creation of the State of Israel in 1948 is the greatest success of all the 20th century movements of national liberation. The full prayer for the State of Israel describes that creation in theological terms as reishit tzi’mihat ge’ula-teinu – the beginning of our redemption. Yet suddenly, in denial of all truth, popular narrative today has transformed Israel into the worst villain of all nations. It’s not just the Soviet accusation that Israel has been transformed from the David resisting the Arab Goliath into the monstrous Israeli Goliath persecuting the poor Palestinians. Now, Israel is accused of being a nation of colonialist settlers, practitioners of apartheid and genocide, white Jewish supremacist oppressors of defenseless Palestinians.

Even many Jews are persuaded by these accusations. A recent poll says that 25% of American Jews believe that Israel is an apartheid state. Twenty-two percent believe that Israel is committing genocide. Twenty-two percent more are undecided. And nine percent believe that the State of Israel should not exist. Again: these are opinions of Jews living in America! Why don’t they know that the charge of genocide is false? That in 1967, when Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza, there were a million Palestinians and that today there are five million Palestinians living in those areas?

Why don’t they know that the accusation of white Jewish supremacy is false? That two-thirds of Israelis are people of color and that 15-20 % of American Jews are people of color as well?

Those who believe these lies are victims; they have been taken in by ideologically driven narratives that are unconnected to reality. One of these is the official narrative of the Black Lives movement that pillories Israel and distorts the truth beyond recognition. Another narrative uses critical race theory to reduce Jews to white oppressors. A third is the internationalization of intersectionality that has compassion for everyone except Jews. Yet another narrative merges anti-Zionism into antisemitism. Net: all Jews are guilty, even those who subscribe to these devastating interlinked narratives. And yes, I am dealing only with the left today because of my deep disappointment with the naivete of Jewish progressives and the relative silence of people who should be our allies.

Now, let’s look at the future by way of an imperfect analogy. Nissim de Camondo, the son of a wealthy French Jewish family, was a fighter pilot in World War I. After he was killed in action, his father, Moise, deeded the family’s grand Parisian home to the French State. Despite the high status of the family (they were married to richest Jewish families, the Rothschilds and the Ephrusis), and despite the fact that France had been the first modern European country to grant the Jews full civil rights, during the Second World War, the Nazi-backed Vichy government arrested the surviving members of the Camondo family and sent them to Auschwitz. The official record says that the de Camondos died for France. But the truth is that they died because of France.

The Nissim de Camondo Museum still exists in Paris, but only a tiny plaque makes these connections. It is clear that the nation that the Camondos loved savagely betrayed them. (David Bell, New York Review of Books, July 1, 2021)

In an eerie contemporary parallel, a young French woman of mixed North African descent, offended by French racism, is quoted in yesterday’s New York Times as saying: “I often say that I’m in love with a republic that doesn’t love me.”

What are the implications for American Jews? Most American Jews still think that we are safe. But so did French Jews. So did German Jews. So do Argentinian Jews. So do Venezuelan Jews.

If Jews are merely tolerated in Western countries despite our patriotism, despite our cultural, scientific and economic contributions, what is our future?

I wish I could talk in terms of sweetness and light. On this Shabbat, when the Torah reading includes the Ten Commandments, I would have preferred to include Mark Twain’s praise “Concerning the Jews” (as Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz of Congregation Kehillath Jeshurun of Manhattan is doing this Shabbat), but I cannot.

This what Mark Twain wrote in an article for Harper’s Magazine in 1898:

“To conclude. —If the statistics are right, the Jews constitute but one per cent of the human race. It suggests a nebulous dim puff of star-dust lost in the blaze of the Milky Way. Properly the Jew ought hardly to be heard of; but he is heard of, has always been heard of … He has made a marvellous fight in this world, in all the ages; and has done it with his hands tied behind him. He could be vain of himself, and be excused for it. The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, then faded to dream-stuff and passed away; the Greek and the Roman followed, and made a vast noise, and they are gone; other peoples have sprung up and held their torch high for a time, but it burned out, and they sit in twilight now, or have vanished.

“The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts, no slowing of his energies, no dulling of his alert and aggressive mind. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

I need to put the dark story I have sketched out here together with Mark Twain’s optimistic vision. Doing so, enables me to remain a prisoner of hope. As Shaul Tchernichovsky, an early 20th century Jewish poet, wrote: A-ah-minah gam b’atid – “I still believe in the future.”

How can we reconcile our traditional literature of consolation and hope with the dark reality that seems to be emerging?

Commence worrying. Details to follow.

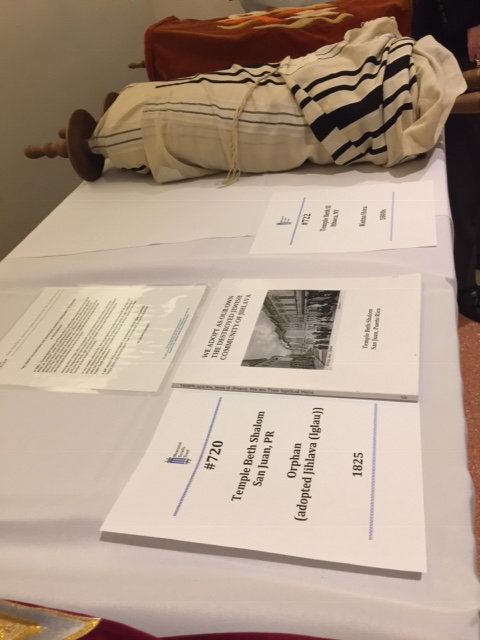

Sometimes, however, an event occurs that brings the story vividly back to our attention. Such an event occurred this past Tuesday night at Temple Emanuel in New York City. The invitation to the event went out by email. There was no other public announcement, and yet there was an astonishing response. Congregants from 75 congregations responded to the call for a gathering of Czech Holocaust Torah scrolls and they came – by car, taxi, bus, plane, train and even on foot – mostly from the tri-state area (NY, NJ and CT), but also from synagogues throughout New England and Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. and Virginia and other states in the southeast. The furthest scroll was brought from Washington State. Naomi and I were there representing two congregations. We brought the Torah scroll from D’vur Kralove which has been in the possession of our New Jersey congregation since 1975, and we brought a short printed history of the Torah scroll in our ark here at Temple Beth Shalom, scroll #720, and a copy of WE ADOPT AS OUR OWN THE DESTROYED JEWISH COMMUNITY OF JIHLAVA, the 134 page monograph about Jihlava and our own Holocaust losses that our congregation published in 2010.

Sometimes, however, an event occurs that brings the story vividly back to our attention. Such an event occurred this past Tuesday night at Temple Emanuel in New York City. The invitation to the event went out by email. There was no other public announcement, and yet there was an astonishing response. Congregants from 75 congregations responded to the call for a gathering of Czech Holocaust Torah scrolls and they came – by car, taxi, bus, plane, train and even on foot – mostly from the tri-state area (NY, NJ and CT), but also from synagogues throughout New England and Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. and Virginia and other states in the southeast. The furthest scroll was brought from Washington State. Naomi and I were there representing two congregations. We brought the Torah scroll from D’vur Kralove which has been in the possession of our New Jersey congregation since 1975, and we brought a short printed history of the Torah scroll in our ark here at Temple Beth Shalom, scroll #720, and a copy of WE ADOPT AS OUR OWN THE DESTROYED JEWISH COMMUNITY OF JIHLAVA, the 134 page monograph about Jihlava and our own Holocaust losses that our congregation published in 2010. Now, from 1964, when the Memorial Scrolls Trust started distributing the scrolls to congregations around the world, until 1969, when Communism collapsed, Cold War fears kept these congregations with Czech scrolls from knowing anything about their scrolls except the name of the town from which the scroll had come. No information about the Jews who had been deported. None of their names, their ages, their stories, or where they were murdered. Nor did we know if scrolls from the same Czech congregation were in the possession of other synagogues in the West.

Now, from 1964, when the Memorial Scrolls Trust started distributing the scrolls to congregations around the world, until 1969, when Communism collapsed, Cold War fears kept these congregations with Czech scrolls from knowing anything about their scrolls except the name of the town from which the scroll had come. No information about the Jews who had been deported. None of their names, their ages, their stories, or where they were murdered. Nor did we know if scrolls from the same Czech congregation were in the possession of other synagogues in the West. Since then, it has all changed. And this event, with a procession of 75 scrolls witnessed by more than 800 people, was a brilliant and moving affirmation of Jewish memory.

Since then, it has all changed. And this event, with a procession of 75 scrolls witnessed by more than 800 people, was a brilliant and moving affirmation of Jewish memory. As participating congregations came in with their scrolls, the excitement as tangible – and mounted. People immediately started telling each other their stories – where their scroll came from, how their congregation learned about the Trust, how the scroll came into their possession, if their scroll was kosher or so defiled that it could not be used but only put on display, what they have been doing over the years to honor their scroll and the memory of the Jewish community of which in many cases the scroll is the only survivor. People compared the mantle designs and described the crowns and pointers (which they had not brought with them, per the instructions of the gathering’s organizers).

As participating congregations came in with their scrolls, the excitement as tangible – and mounted. People immediately started telling each other their stories – where their scroll came from, how their congregation learned about the Trust, how the scroll came into their possession, if their scroll was kosher or so defiled that it could not be used but only put on display, what they have been doing over the years to honor their scroll and the memory of the Jewish community of which in many cases the scroll is the only survivor. People compared the mantle designs and described the crowns and pointers (which they had not brought with them, per the instructions of the gathering’s organizers). The main feature of the event was a solemn procession of scrolls down the center aisle of the room to the stage while the entire assembly stood and a violinist played variations on Hatikvah. Three rows of Torah scrolls were displayed. Some 800 people, many photographing and almost everyone with tears in their eyes.

The main feature of the event was a solemn procession of scrolls down the center aisle of the room to the stage while the entire assembly stood and a violinist played variations on Hatikvah. Three rows of Torah scrolls were displayed. Some 800 people, many photographing and almost everyone with tears in their eyes. In this week’s parashah, Terumah, Moses calls upon the Israelites to make contributions to build the tabernacle. The verse invites kol ish asher yid’venu libo — every person whose heart is willing (Exodus/Shmot 25:2) – to make contributions. When we read the names of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Jihlava we are performing a service of the heart. And that is one important way the verse that follows in the Torah portion – v’asu li mikdash v’shakhanti b’tokham – let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell in their midst (Shmot/Exodus 25:8) – is fulfilled. That verse is on the wall of this sanctuary. But it is the devotion of willing hearts that makes our congregation, at its best, a place and a people holy to God.

In this week’s parashah, Terumah, Moses calls upon the Israelites to make contributions to build the tabernacle. The verse invites kol ish asher yid’venu libo — every person whose heart is willing (Exodus/Shmot 25:2) – to make contributions. When we read the names of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Jihlava we are performing a service of the heart. And that is one important way the verse that follows in the Torah portion – v’asu li mikdash v’shakhanti b’tokham – let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell in their midst (Shmot/Exodus 25:8) – is fulfilled. That verse is on the wall of this sanctuary. But it is the devotion of willing hearts that makes our congregation, at its best, a place and a people holy to God.