Anticipating Springtime in Israel

Tu B’Shevat is our next festival!

Our Temple Beth Shalom Tu B’shevat seder will be on Wednesday evening, January 27th (Erev Tu B’Shevat) via Zoom. Watch for the announcement and the link.

Read on!

Introducing Tu B’Shevat

Tu B’Shevat is the festival that welcomes the beginning of springtime in Israel. The rainy season has ended. Fragrant, beautiful white petals are in blossom on the almond trees. It has grown warm already in the Galilee.

Over the centuries, Jewish communities around the world, and particularly in Europe, observed Tu B’Shevat as a reminder of our people’s ongoing connection with the Land of Israel. Their custom was to eat as many of the fruits of the Holy Land as could be purchased wherever a Jewish community lived. Particularly treasured was the fruit of the carob tree, known in Hebrew as haruv and in Yiddish as bokser, rarely available anywhere in Northern Europe (or even in the US) other than as dry, hard pods. (The carob is also known in English as St. John’s bread.)

In the 16th century in the Land of Israel, Rabbi Yitzhak Luria of Safed and his disciples created a Tu B’Shevat seder, somewhat like a Passover seder, that celebrated the Tree of Life. The seder, still the principal observance of the hag, evokes Kabbalistic themes of restoring cosmic blessing by strengthening and repairing the Tree of Life, generally using the physical metaphor of a tree: roots, trunk, branches and leaves. The traditional Tu B’Shevat seder ended with a prayer which states in part, “May all the sparks scattered by our hands, or by the hands of our ancestors, or by the sin of the first human against the fruit of the tree, be returned and included in the majestic might of the Tree of Life.”

The main feature of the seder is a platter of fruit, eaten dried or fresh, divided up from lower or more physical to higher or more spiritual, as follows:

- Fruits and nuts with hard, inedible exteriors and soft edible insides, such as oranges, bananas, walnuts, and pistachios.

- Fruits and nuts with soft exteriors and a hard pit inside, such as dates, apricots, olives and persimmons

- Fruit which can be eaten entirely, such as figs and berries.

Kabbalistic tradition teaches that by eating fruits in that order one travels from the most external or manifest dimension of reality, symbolized by fruits with a shell, to the innermost dimension, symbolized not even by the completely edible fruits but rather by a fourth very esoteric level that may be likened to smell. The Kabbalistic “seder” ritual also involves drinking four glasses (or sips) of wine in an oenologically unsophisticated manner – all from white to a mix of white and red, to red and white, to all red, also corresponding to the external-to-internal levels. It is customary to include the Torah-designated seven species – wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates – among the offerings on the seder plate.

Another name for Tu B’Shevat is the New Year of the Trees, Rosh Hashanah la-Ilanot. According to the Mishnah (Rosh Hashanah 1:1), there are four new years in the Jewish calendar. The other three are the first of Nisan, the new year for kings and festivals; the first of Elul, the new year for the tithing of animals; and the first of Tishri, which we celebrate as Rosh Hashanah, the beginning of a new year (despite the fact that technically it is the seventh, not the first month of the Jewish calendar) and observe with elaborate synagogue ritual featuring the blowing of the shofar and soul-searching prayer.

And now, an aside to share with you a complicated explanation of what is otherwise a simple ecological and agricultural-based festival: the meaning of the first word of the name Tu B’Shevat itself.

More than 2,000 years ago, each of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet was given a numerical value. To this day, these values are used as an alternative to arabic numerals. This numerical system is a decimal system, based on the number 10. Thus, aleph equals 1; bet = 2, and so forth. The “T” of Tu = tet is thus the ninth letter of the alphabet, equalling the number 9. The “u” (a stand-in for the letter vav to make a pronouncable word) is the sixth letter of the alphabet, equalling the number 6. Therefore, tet and vav together, 9 + 6 = 15. With us so far?

Then why 9 + 6 = 15 rather than 10 + 5? Glad you asked. The answer finesses an inherent theological problem because yod plus hey together spell one of the names for God: YAH, as in halleluYAH – praise be to God. Our ancestors could not combine the letters yod (10) and hey (5) to equal the number 15 because it spelled out one of the names for God and was therefore sacred. So they substituted the numbers 9 and 6 to get to 15. * (There will not be a quiz on the subject, but see the note below for additional explanation.)

Carob pods are sometimes available to Hebrew schools on the mainland today, but they were prized possessions of congregations in the late 1940s and ‘50s. The fruit was rock-hard and most of us found the flavor unpalatable. In recent decades, carob has not only become more common but for many years was considered a reasonable chocolate substitute. The Patzes have a bottle of carob syrup they purchased in Sicily last year, forgot to bring with them to San Juan for their Tu B’Shevat celebration and are looking forward to checking it out this January 28th. (And if we don’t use it now, we’ll try to remember to bring it next year, Covid-willing. We will keep you posted.)

Carob pods are sometimes available to Hebrew schools on the mainland today, but they were prized possessions of congregations in the late 1940s and ‘50s. The fruit was rock-hard and most of us found the flavor unpalatable. In recent decades, carob has not only become more common but for many years was considered a reasonable chocolate substitute. The Patzes have a bottle of carob syrup they purchased in Sicily last year, forgot to bring with them to San Juan for their Tu B’Shevat celebration and are looking forward to checking it out this January 28th. (And if we don’t use it now, we’ll try to remember to bring it next year, Covid-willing. We will keep you posted.)

Interesting carob trivia: Carob seeds have a nearly uniform weight of 0.2 grams. Ancient civilizations used the seeds as a reference weight for precious gemstones: one carob seed equals one carat; one carat equals 0.2 grams. A diamond weighing 100 carats weighs 20 grams, which is about the same as 100 carob seeds. To this day they continue to be the name and unit of weight for diamonds.

Currently In The Museum Case Of Our New Jersey Congregation

And Brought To You Virtually

With Love

The technical name for this flower is Lupinus Pilosus. It is more commonly known as a lupine.

The wild mountain lupines, endemic to Israel cover the sides of the roads and color the hillsides with silver leaves and refreshing deep blue blossoms from February to May – a stunning, seemingly endless display of blossoms.

Botanists are not yet certain about how the plant has spread so widely. Its seed is heavy, unpleasant tasting and rather toxic. How, therefore, has it succeeded in spreading the way it has when animals avoid eating the seeds due to their toxicity and bitterness and therefore don’t take part in the dispersal process? And because the seeds are especially big and heavy, they are not blown by the wind. But the prevailing botanical view today is that the great weight of the seeds themselves is responsible for the pattern of the plants’ distribution. Basically, the secret is that the seeds’ dispersal is limited to its immediate surroundings and that it moves slowly but inexorably toward widespread dispersal. The sources explain that Newton’s theory of gravitation is responsible: this dispersal type, called “stain dispersal” by botanists, move from the center outwards while the stain’s radius grows larger year by year. Obviously, seeds that fall and blossom within the stain’s perimeter would be those that cause its growth. And it grows and spreads and grows and spreads and gives the appearance of a giant carpet along the roadside throughout the spring.

Lupines played an important dietary role in ancient Israel. Even today, lupine beans are offered for sale in the Old City of Jerusalem and other Arab markets. Though bitter to the taste, they are very palatable after prolonged boiling, inexpensive, and a good source of minerals, such as calcium, phosphorus, and iron. (Noting, not recommending.)

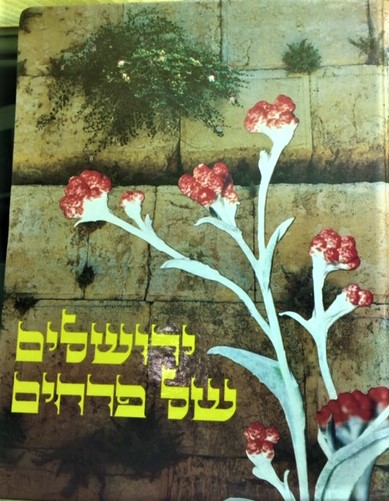

On the cover of this book, Yerushalayim shel Perahim (Jerusalem of Flowers), by Yaakov Skolnick, is a flower whose Latin name is helichrysum sanguinum. It is known in Hebrew as Dahm HaMaccabeem Ha-Adom – “the red blood of the Maccabees.” This flower (despite appearances, a member of the daisy family), is also known as Red Everlasting.

Like the poppy in our country and in England on Memorial Day, the flower serves as a symbolic reminder on Yom HaZikaron, Israel’s Memorial Day, of the fallen soldiers and the victims of terrorism. The flower in the picture above is superimposed on a section of the Western Wall in Jerusalem, visually uniting prayers for peace and healing with an expression of grief for those lost. The bush which juts out of the wall is a caper plant, many of which grow in the wall’s crevices.

From Ancient To Modern Times:

Jewish Respect For And Love Of Nature

For Jews, Ecology Is Not A New Subject Of Concern

In Sh’mot/Exodus, the Torah calls Israel “a land flowing with milk and honey” (3:8).

In D’varim/Deuteronomy, there is a specific prohibition on cutting down the trees of a city being besieged in wartime: “When in your war against a city you must besiege it for a long time in order to capture it, you must not destroy its trees…. You may eat of them, but you must not cut them down. Are trees of the field human to withdraw before you under siege?” (20:19). This prohibition is the legal and moral basis for the outcry in Israel on the rare occasions when Israeli troops destroy trees (particularly fruit trees and especially ancient olive trees) in their pursuit of Arab terrorists.

In Ketuvim/Writings, the third section of the Bible, Psalms and the Song of Songs are replete with imagery from nature expressed in imaginative and poetic ways. To give just a few examples:

Psalm 92 says, “The righteous shall flourish like the palm, grow tall like cedars in Lebanon, rooted in the house of the Eternal they shall be ever fresh and green….”

And Psalm 98, “Let the sea and all within it thunder, the world and its inhabitants; let the rivers clap their hands, the mountains sing joyously together at the presence of the Eternal.”

There are a great many nature images in Song of Songs:

“I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys. Like a lily among thorns, so is my darling among the maidens” (2:1-2).

And later in the same chapter, “For lo the winter is passed, the rains are over and gone. The blossoms appear in the land, the time of pruning has come; the song of the turtledove is heard in our land. The green figs form on the fig tree, the vines in blossom give off fragrance” (2:11-13).

Chapter 7:12-13 says: “Come my beloved, let us go into the open; let us lodge among the henna shrubs. Let us go early into the vineyards; let us see if the vine has flowered, if its blossoms have opened, if the pomegranates are in bloom; there I will give my love to you.”

Nevertheless, since the 19th century, there have been consistent and repeated attacks on Jews and Judaism as being insensitive to the natural world. The concept may come from the fact that over the centuries in most countries Jews were not allowed to own or work the land or perhaps from drawings and paintings of bearded Talmud scholars bent nearsightedly over piles of religious texts with no countervailing illustrations of Jews involved in nature. Or perhaps it is just another example of groundless hostility to Jews and Judaism, an aspect of the newly developed 19th century racial antisemitism which led inexorably to the disaster of the Holocaust.

The truth is otherwise. From the Bible on, Jewish texts and practice are suffused with love of nature and respect for it. Tu B’Shevat itself is an example of how Jews over the centuries combined their awareness of the world around them with longing for the Israel they had never known.

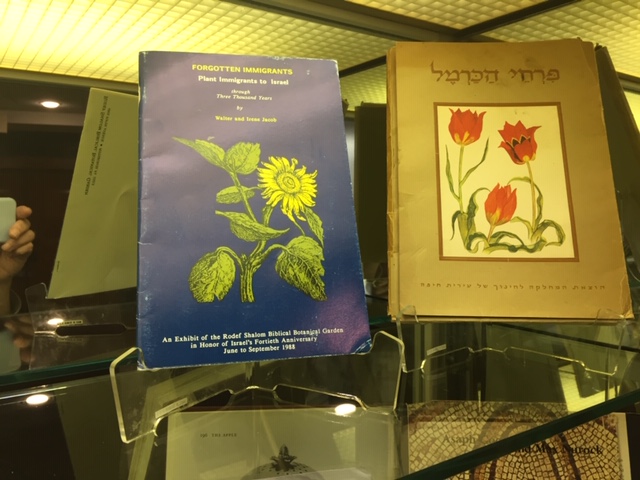

FORGOTTEN IMMIGRANTS, the book pictured here, celebrates the creation of a “biblical botanical garden” at Rodef Shalom Congregation in Pittsburgh, PA in honor of the 40th anniversary of the State of Israel. The garden, established in 1987 on a third of an acre, features more than 100 different kinds of temperate and tropical plants, including plants named in the Bible as well as numerous others that have been given biblical names. The pastoral setting has a cascading waterfall, a desert, a bubbling stream known as “the Jordan,” which meanders through the garden from “Lake Kinneret” to the “Dead Sea.” All of the plants are labeled with appropriate biblical verses and are displayed among replicas of ancient farming tools. Among the specimens are wheat, barley, millet and herbs valued by the ancient Israelites. Olives, dates, pomegranates, figs, and cedar trees round out the historic and educational inventory.

FLOWERS OF THE CARMEL: Although Israel is a very small country, no larger than the State of New Jersey, it is blessed with an extraordinary number of microclimates. Their flora and fauna range from forested mountain ranges to deserts and wilderness in the Negev. Pirkhei Ha-Carmel, published by the Haifa Municipality in 1958, is devoted to The Flowers of the Carmel. It contains 32 brilliant illustrations by Brachah Levy of flowers that bloom in the Galilee (of which the cover photo is one). The mountainous Carmel region extends south and east from Haifa into the heartland of the Galilee.

Incidentally, the area – especially the caves in the Carmel mountains – was home to settlement by humans in Neolithic times. Evidence from numerous Natufian burials and early stone architecture represents the transition from a hunter-gathering lifestyle to agriculture and animal husbandry that, years ago, at least, provided a setting for successful foraging for prehistoric arrowheads fashioned from stone (broken but identifiable).

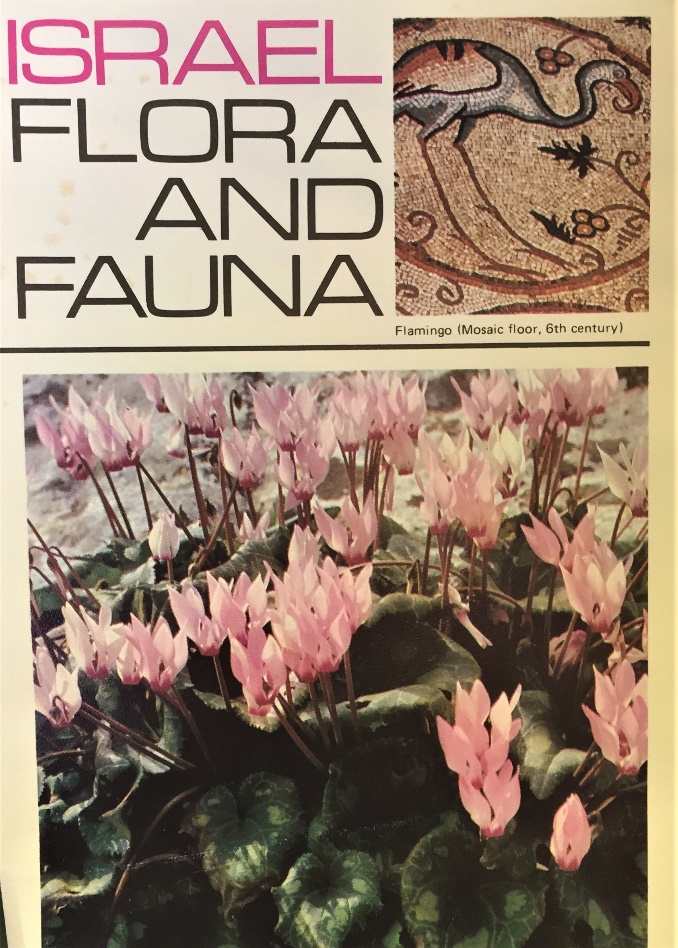

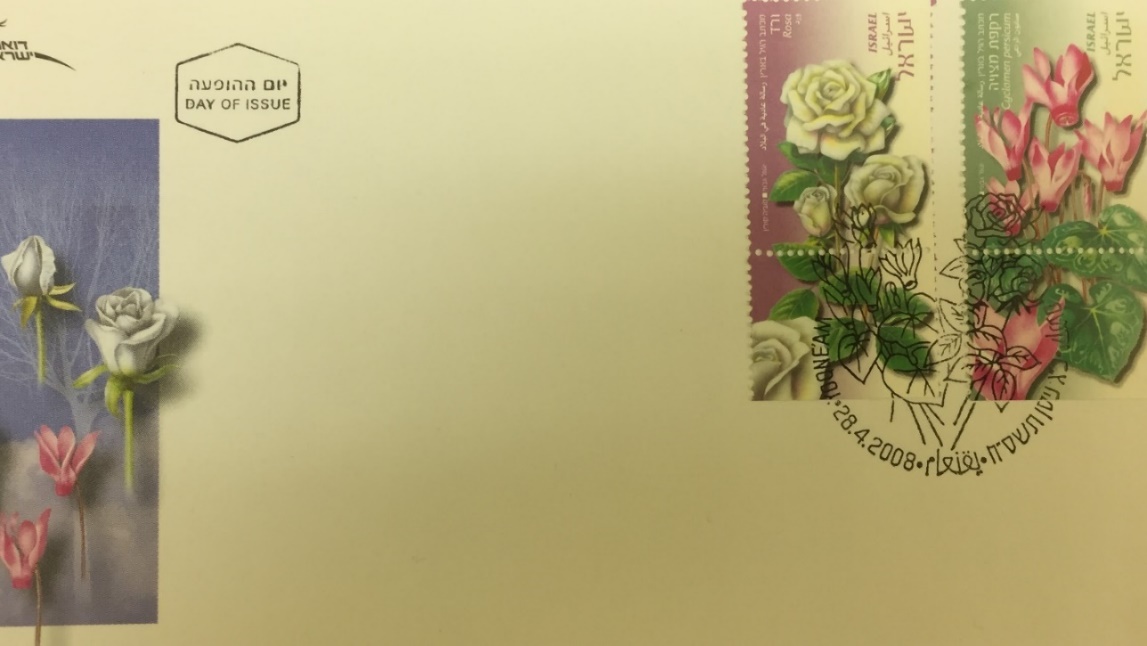

In 2007, the cyclamen – RAKEFET in Hebrew – was named the national flower of Israel. It is a winter flower that usually blooms between December and February. Note that its petals flare upward; the flower has evolved upside down to protect its stamens and pistil from the cold raindrops of early spring.

The pen and ink drawings above, by the noted calligrapher Betsy Platkin Teutsch, appeared in the April 1987 issue of In Process, a publication of the United Jewish Appeal Young Leadership Cabinet edited by Naomi Patz, in honor of the Passover season: “… now that the winter is passed and the rains are over and gone.” The flowers are (l to r) rakefet (cyclamen), narkis (narcissus) and eeroos (iris).

The first stamp above, a map of Israel, carries the date November 30, 1947 and was issued immediately after the United Nations Partition decision of the day before. Bearing the name Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael (which we know as the Jewish National Fund), the large Hebrew letters across the top and down the left say “the State of the Jews” rather than the name of the new country, which was not decided until six months later. In fact, the name was still being debated barely minutes before David Ben Gurion proclaimed statehood!

The stamps we have assembled here (some of our earliest) all celebrate one way or another the return of warm weather. The first stamp in the second row and the first four stamps in the bottom row combine flowers with iconic images of modern Israeli military history: Yehi-am, Yad Mordecai, Kibbutz Degania, a tribute to fallen soldier in Tzefat, and the aqueduct at Gesher Haziv. (Look them up online; each is associated with a significant battle in Israel’s War of Independence.)

Israeli stamps are trilingual, in Arabic, English and Hebrew, following the practice of the British Mandate of Palestine (as required by the League of Nations). In its earliest years, Israel issued stamps picturing the Jewish holidays, Jerusalem, Petah Tikva, the Negev, the Maccabiah Games and Independence bonds. Every year, Israel issues a festival series to commemorate the regalim, the pilgrimage festivals – Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot. In 1952, Israel issued its first stamp honoring a named person, Chaim Weizmann. Other honorees of the 1950s included Theodor Herzl, Edmond de Rothschild, Albert Einstein, Sholem Aleichem, Hayim Nahman Bialik and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. The first woman honored was Henrietta Szold (1960), the first rabbi was the Baal Shem Tov (1961), and the first non-Jew was Eleanor Roosevelt (1964).

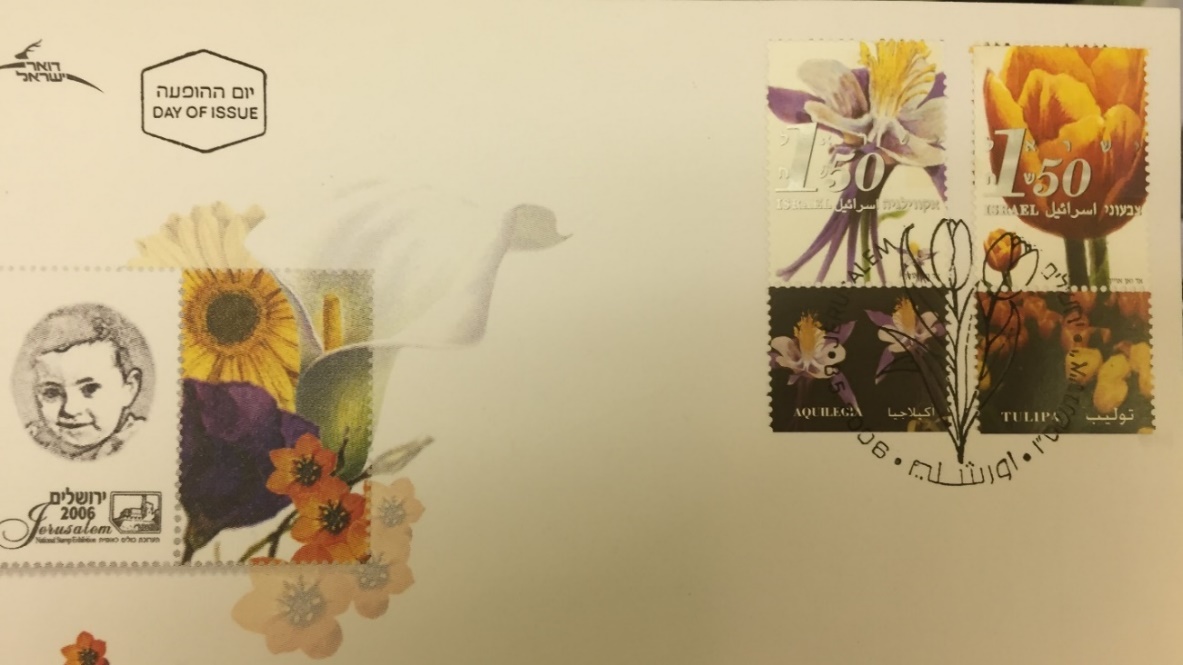

A first day of issue cover or first day cover, like the ones below, is a postage stamp on a cover, post card or stamped envelope franked on the first day of its issue. Its purpose is a combination of expressing pride in individuals and events and earning revenue for the postal service.

Two Flower-shaped Havdalah Spiceboxes And One In The Shape Of An Apple

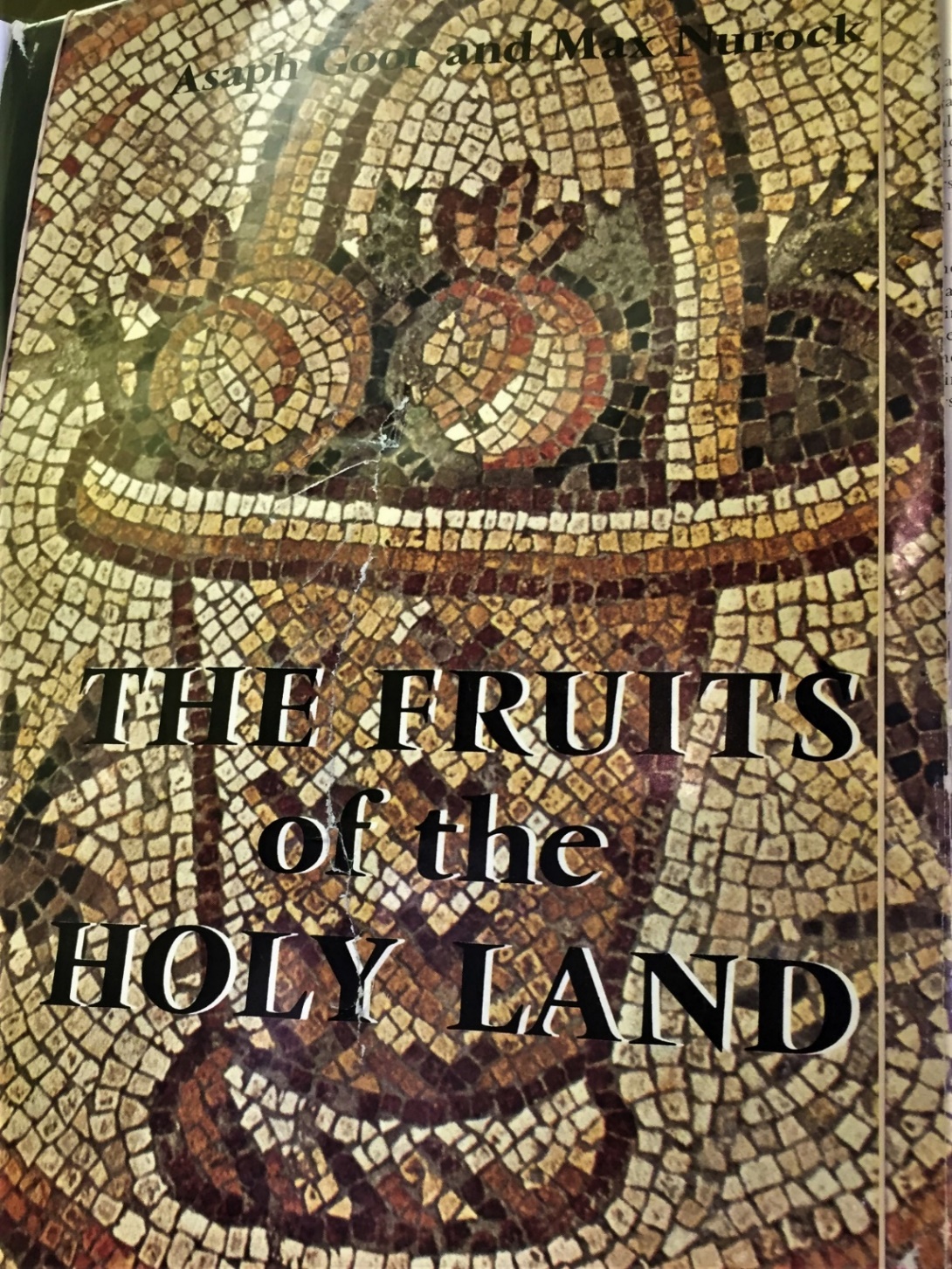

The Fruits of the Holy Land, by Asaph Goor and Max Nurock, traces the history of the fruits of the Bible, the Mishnah and the Talmud, drawing freely on many sources. It is illustrated by reproductions from manuscripts, woodcuts, paintings, sculptures and mosaics throughout the centuries. The cover art shows a basket of pomegranates, a fragment of a magnificent mosaic floor from the sixth century C.E. Maon synagogue and archaeological site in the Negev, near Kibbutz Nirim and Kibbutz Nir Oz. The Maon Synagogue is one of many synagogues built in the 6th and 7th centuries C.E. in both the north and south of Israel. Their existence testifies to the fact that Jews continued to live openly and flourishing throughout Israel in the centuries following the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E.

This certificate, most likely from the 1920s, is a rare example of a document acknowledging the gift of one dunam of land purchased from Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael, the Jewish National Fund. A dunam equals one-quarter of an acre; the wedding present was in effect, therefore, a symbolic investment in the land of Israel by (and perhaps for) people for whom the rebuilding of Israel was of central concern. The large title in the rectangle above translates as “The Contribution of a ‘Portion’ (or ‘Inheritance’) of Keren Kayemet L’Yisrael.” The Hebrew phrase on the left says “This is the land which will be yours as an inheritance” (B’midbar/Numbers 34:2). The name of the donor(s) does not appear and no date is given, but the bride and groom are Barnett and Esther Bernstein. Their dunam of land is identified by its registration number.

The photograph above was taken sometime during the early 1920s at a moshav in the central part of British Mandate Palestine. The second man from the left in the front row, wearing a cap, is Naomi’s great uncle Alex Golden. One of the sons of a very Zionistic family, Alex went from Lakewood, New Jersey to join the Thirty-Ninth Royal Fusiliers, a battalion of the British Army known as the G’dud – the Jewish Legion. The Jewish Legion (1917–1921) consisted of five battalions of Jewish volunteers, the 38th to 42nd Royal Fusiliers in the British Army, formed to fight against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War. The G’dud was the brainchild of Zeev Jabotinsky and Joseph Trumpeldor: a military unit of Jews that would take part in the British effort to capture Palestine from the Ottoman Empire. The British Army accepted 650 Jewish volunteers into the group, which they named the Zion Mule Corps. Five hundred and sixty two of its members served in the Gallipoli Campaign. Later, they saw action in the Jordan Valley under General Allenby. Former members of the Legion took part in the defense of Jewish communities during the riots in Palestine of 1920, which resulted in Jabotinsky’s arrest and the final disbanding of the Legion.

Naomi’s uncle Alex had planned to stay on in Palestine and make aliyah. In fact, Naomi’s mother, who was then 10 years old, and her brothers, grandmother and great grandmother, moved there to join Alex, who was living on the moshav in the photograph. But the new arrivals found life on the moshav too difficult and moved instead to Tel Aviv, still a very raw young town where boardwalks instead of sidewalks crossed the as-yet not built up sandy areas leading to the sea. When that too failed because there was trachoma (a devastating eye disease) in the public schools and there was no money to send my mother and her brothers to private school, they very reluctantly returned to the States, and Alex returned with them.

At Moshav Avihayil, near Netanya, where a number of veterans of the Jewish Legion settled, there is a museum devoted to the history of the G’dud,; in the book of the 39th Royal Fusiliers we found the pages honoring Alex Golden.

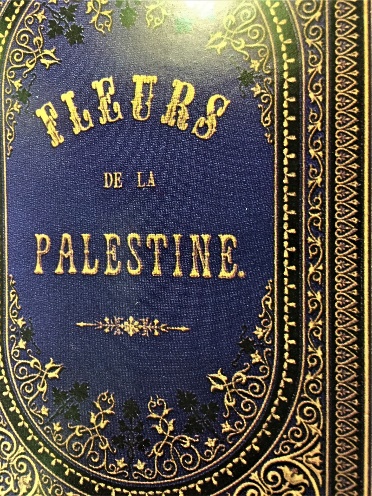

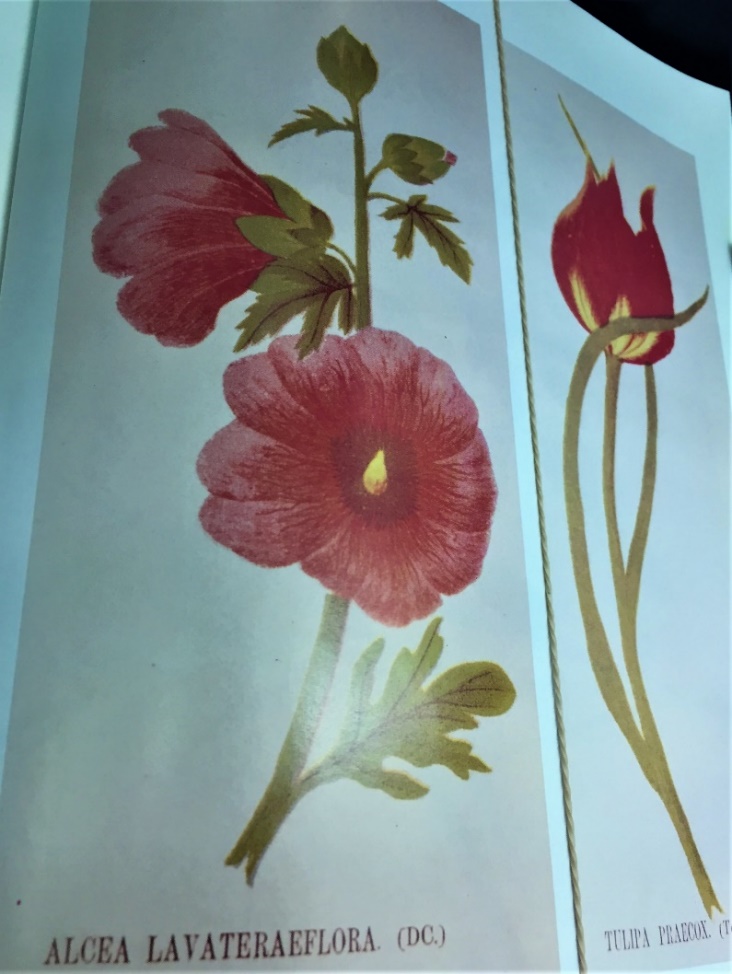

Covers And Interior

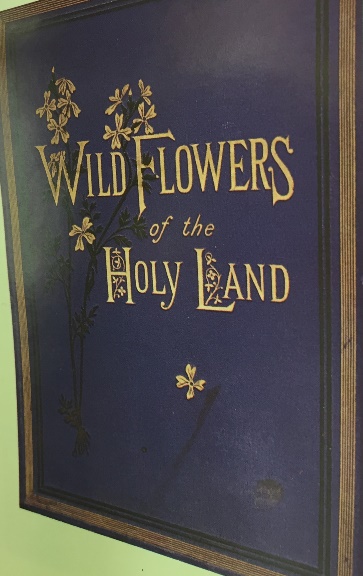

This book, by Hannah Zeller, was published in German, French and English in 1875, making it one of the earliest books to illustrate the flowers of the Land of Israel. The flower on the left in the drawing, Alcea Lavateraeflora, is a member of the hollyhock family; the one on the right is easily identifiable as a variety of tulip.

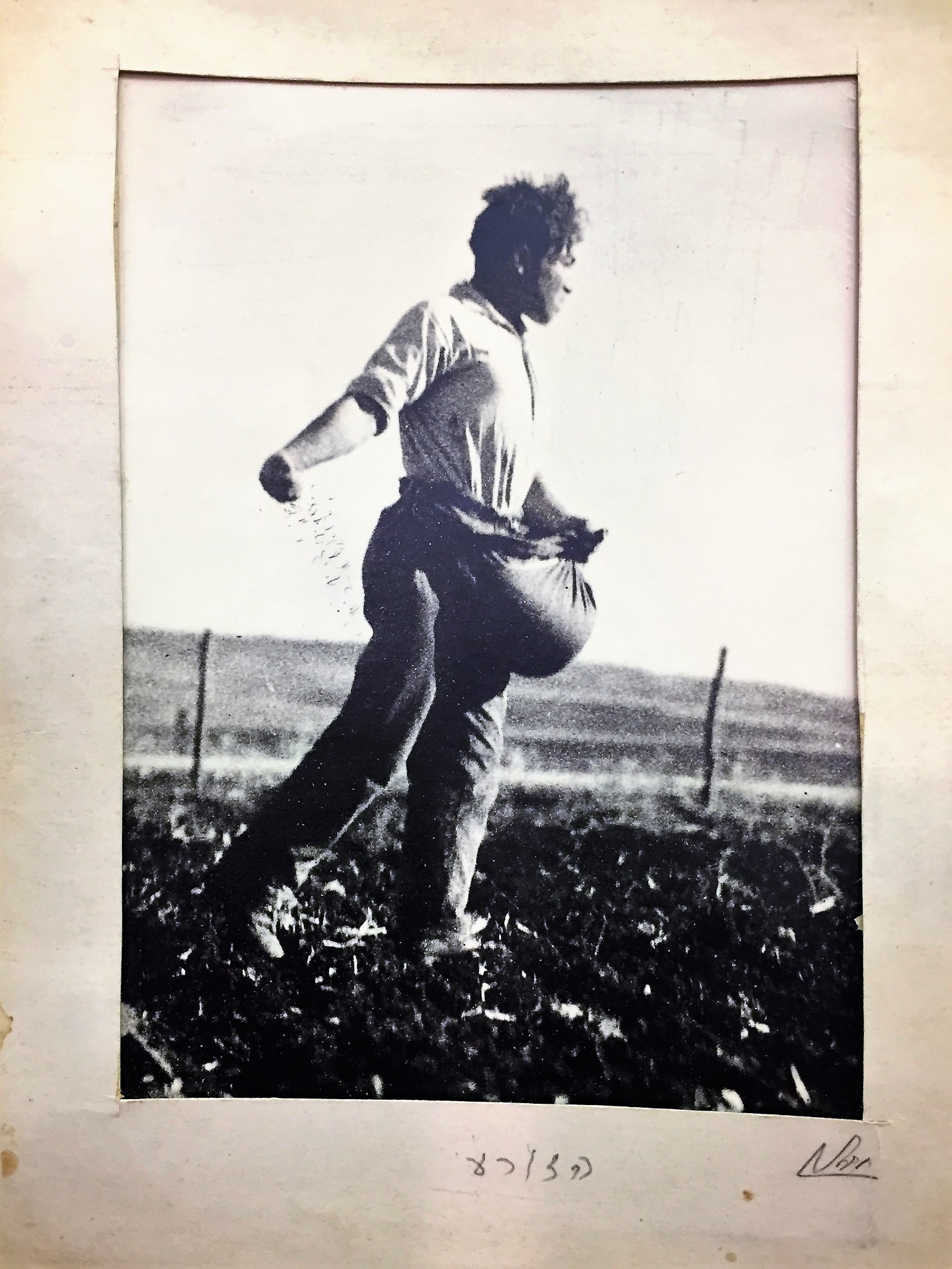

This photograph of HA-HORESH – THE PLOWMAN dates to the same period as that of the sower above. It may be by the same photographer although, while the Hebrew handwriting is the same, we aren’t sure that the signatures match. We also can’t decide if what we see in the background are low-hanging clouds or if the field he is preparing sits above Lake Kinneret (also known as the Sea of Galilee), with the mountains of the Golan Heights visible in the far distance.

The ubiquitous blue box that sat in many of our kitchens and on the counters in Jewish bakeries, butcher shops and delicatessens in the 1940s and ‘50s was the brainchild of a Viennese Zionist named Johann Kremenezski between 1902 and 1907. His “invention” popularized an initiative by Hermann Schapira, a Russian mathematician, Hebraist and Zionist, a visionary thinker who was the first to advocate the idea of a Jewish national fund to purchase land in perpetuity in Palestine in the name of the Jewish people. As early as the first Zionist Congress, in 1897, Schapira, who died very young and long before any of his initiatives were realized, proposed the foundation of a Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Coincidentally, a Polish bank clerk named Haim Kleinman also proposed that a collection box bearing the words NATIONAL FUND be placed in every Jewish home to raise money for land purchases in the homeland.

Per the drawing of the map, the box pictured here is from the period from 1948 to 1967 (before the Six Day War).

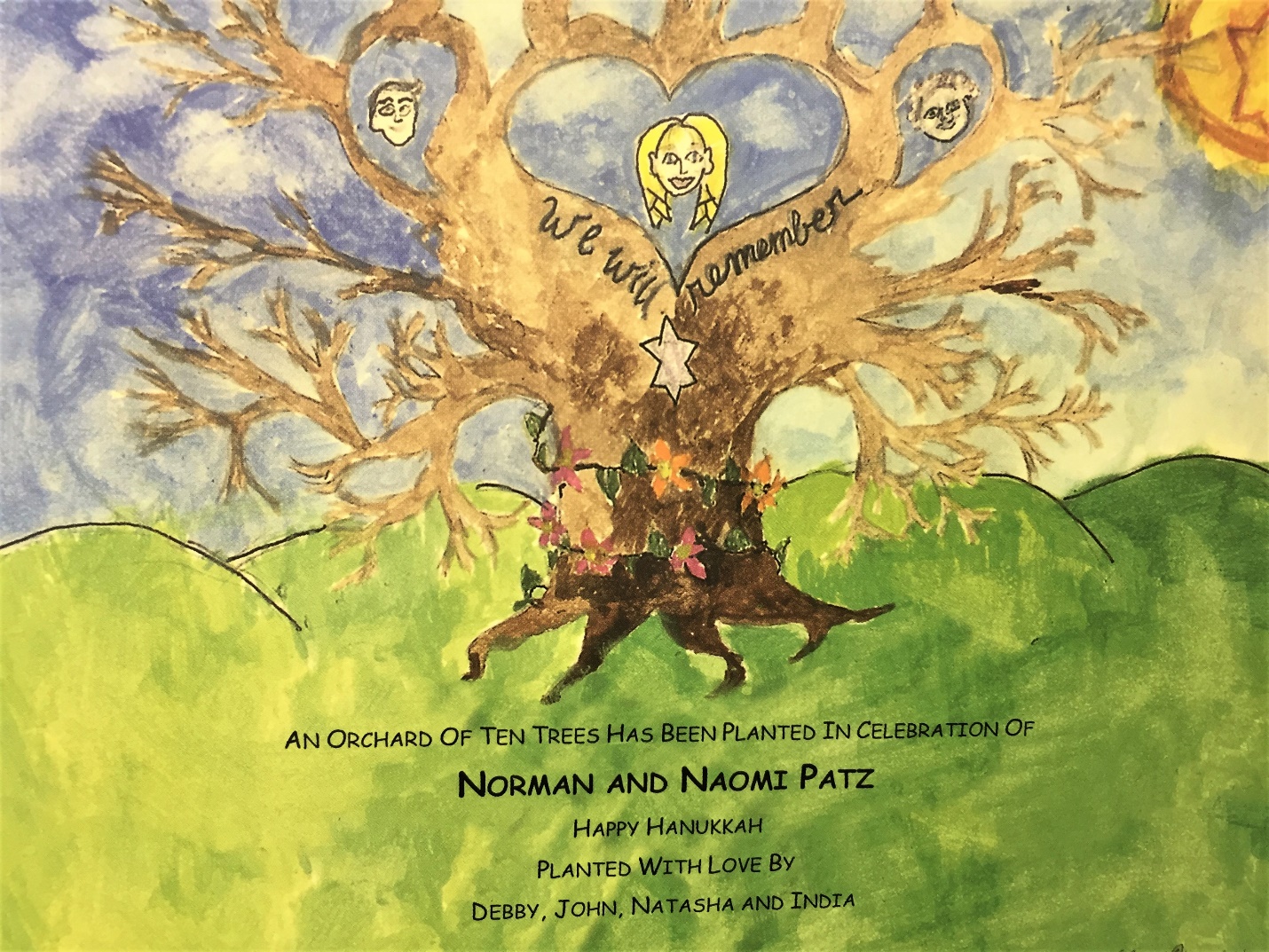

Since its founding in 1901, one of the principal projects of the Jewish National Fund beyond the purchase of land in Palestine has been the reforestation of a land that had been stripped of its trees by neglect and abuse, most particularly by the construction in the late Ottoman period of railroads whose building required huge amounts of lumber. Over the years, tree certificates were sold – in religious schools by students purchasing individual “stamps” to paste onto their symbolic tree outlines, and as honoring gifts for b’nei mitzvah, anniversasries and other special occasions as well as in memory of loved ones. In the 1940s, the cost of a tree was $2.50, roughly the equivalent of today’s $18.00 (chai). Larger purchases, for orchards (as above), gardens, groves and forests have helped the regreening of Israel, the greatest ecological reforestation in history – over 250 million trees have been planted so far!

How do the trees we “plant” actually get into the soil? On Tu B’Shevat, Israeli school children participate in mass tree plantings in JNF forests around the country. In earlier years, such tree planting took place right in the cities. Bilha Barkai, the woman who coordinated our teen trips to Israel over the years, remembered going with her classmates to plant trees on the median divider of Rothschild Boulevard, a broad avenue in the center of Tel Aviv! Tour groups and students on year courses and individual visitors go to the JNF forests to plant. We have taken virtually every one of our teen and adult groups to Israel to plant trees, including in the year when we dedicated a garden of 100 trees contributed by the members of Temple Sholom of West Essex in the name of the congregation. The Jewish National Fund has truly transformed the swamps and deserts of 19th century Israel into the land of milk and honey of which our biblical ancestors wrote.

This curiosity is a Keren Kayemet Israel school project of the 1970s designed to involve Israeli students with a constructive awareness of the natural beauty of their country and, through their effort, to share a feeling of love for and association with the land with students in Jewish Hebrew schools and day schools throughout the Diaspora. This flower, a PEREG – the Hebrew name for poppy –, was picked and carefully dried by a 13-year-old school girl in Tel Aviv named Dalia Botbol (whose name and age are on the back of the presentation folder).

Breathtakingly beautiful poppy flowers grow in abundance all over Israel. Nine separate pereg species can be found, most beginning their bloom season in March, and none lasting past June. The only area of the country whose climate does not support a pereg population is the Negev.

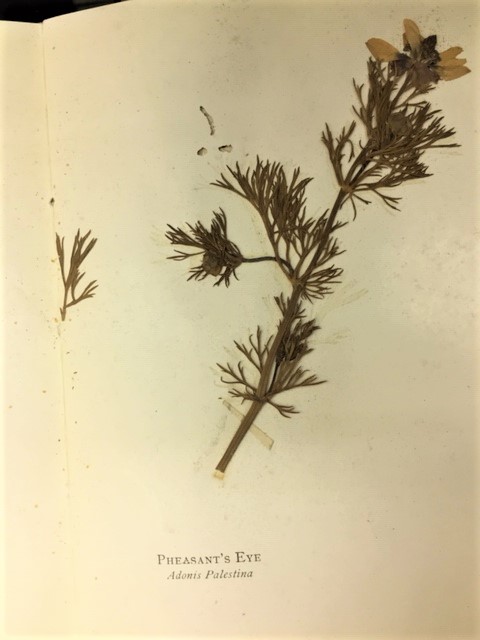

This booklet of pressed flowers (sample interior pages above, cover below) was published in Ottoman Palestine by Smuan Petrus Bordnikoff in 1900. These photographs show two of the steps in the preparation of dried flowers for export to the United States and other countries.

More Pressed Flowers from the Holy Land

This book – with descriptions in German, English, French and Russian – is a souvenir volume of Flowers and views of the Holy Land, Jerusalem. It features 12 chromolithographs depicting various places in the Holy Land, with pressed flowers from that area mounted on each facing plate. It was certainly published prior to World War I since Russian would not have been included post-war owing to the fall of the Czar and the creation of the anti-religious Communist regime that came to be called the USSR. Several different versions of the title survive in both university and private libraries, not all showing identical varieties of flower. Produced by various publishers and apparently very popular with pilgrims and other tourists, the books were almost all uniformly bound in covers of polished olive wood from the “Holy Land” and decorated with an inlaid geometric border surrounding the word Yerushalayim in Hebrew and Jerusalem in Latin letters. At least one such book was made during the First World War for the British troops in Jerusalem as a “souvenir” of their occupation.

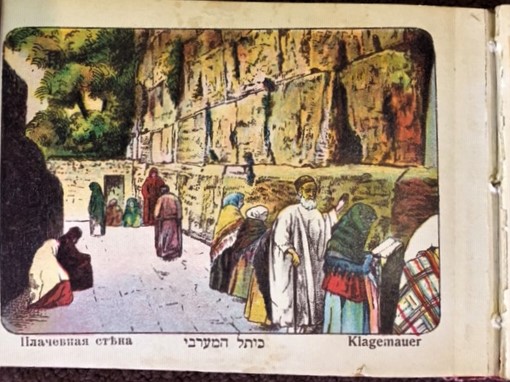

The illustration on the left shows people praying at the Wall in Jerusalem. The text beneath it reads Kotel Ha-ma-a-ravi – the Western Wall – in Hebrew (center, which is what the Wall was always called in Hebrew), and Klagemauer – the Wailing Wall – in German and presumably the same in Russian (Russian readers: please correct us if we are wrong!). The text above the pressed flowers on the right reads, in Hebrew, “Flowers of the Western Wall,” and below, in German followed by the same in English, French and Russian: “Flowers from the Jews Wailing Place.”

Last, but certainly not least, is another first day cover. This one celebrates a most unusual environmental journey. Back in the 1950s, Lake Huleh – a shallow, swampy breeding ground for malaria-carrying mosquitos – was drained in a huge ecological project overseen by Keren Kayemet and the Israeli government. There was great celebration and the fertile land began to be reclaimed for agricultural productivity. Forty years later, by the late 1980s, it became clear that draining the swamp had been a huge mistake. The effects on the ecosystem, which had not been perceived in the first half of the twentieth century, turned out to be a mixed blessing. Malaria had been eradicated but water polluted with chemical fertilizers began flowing into Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee), lowering the quality of its water. The soil, stripped of natural foliage, was blown away by strong winds in the valley, and the peat of the drained swamp ignited spontaneously, causing underground fires that were difficult to extinguish.

In 1963, a small (3.50 km) area of recreated papyrus swampland in the southwest of the valley was set aside as the country’s first nature reserve. Concern over the draining of the Huleh was the impetus for the creation of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel, which has had a huge positive impact nationwide. By the late 1980s, a full restoration was in the planning and was completed by 1996.

Israel is uniquely situated in the Great Rift Valley that extends from Turkey down into Africa. One of the remarkable features of the location is that it is a major north/south path for migratory birds. The drained Huleh deprived the birds of food and water resources and they diverted their flight patterns, to their own detriment. During the first three years after reflooding, at least 120 species of birds were recorded again in and around the lake, and more have returned since. Migratory pelicans, storks, cormorants, cranes and other birds en route between Europe and Africa spend days to weeks in the vicinity of the Huleh, drawing thousands of bird watchers from around the world. Grazing mammals such as water buffalos are also being returned to the area. The stamps below, on the first day cover issued in 2007, show some of the wildlife that populates the Huleh Valley since the completion of the restoration project.

When are YOU going to Israel?

Now is the time to begin thinking about life post-pandemic.

HAPPY TU B’SHEVAT!

Naomi Patz, Curator

*In order to reach numbers beyond ten, the next eight letters are given number values that increase by a factor of ten from 20 to 90. The final four letters are given number values that increase by a factor of one hundred from 100 to 400. In Hebrew, gematria is often used as an alternative to arabic numerals when recording numbers. Hebrew dates are generally written using gematria. Click here to return.