Our Torah And Jewish Memory – Shabbat Terumah

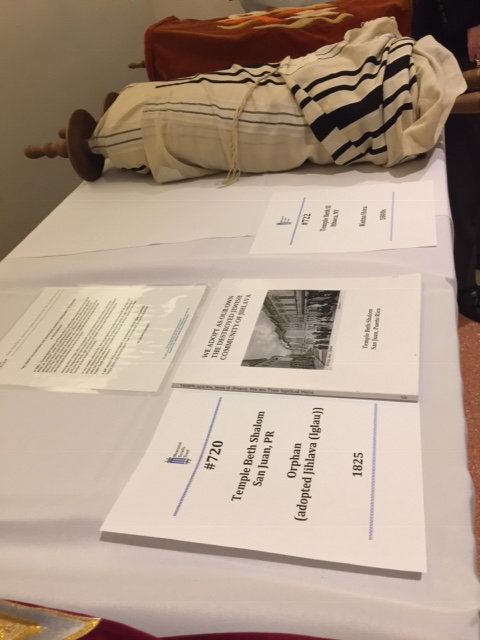

We sometimes get so used to the things around us that we stop seeing them. That is, we don’t consciously remember what the things mean or what they stand for. Consider the two framed documents on the sides of the bimah here. On my right is the document from the Memorial Scrolls Trust in London that records the allocation of Torah scroll #720 to our congregation in 1967, labeling it an “orphan” scroll. On my left, is a second document, from 2010. It describes how our congregation has linked our orphan scroll to the Moravian town of Jihlava.

The framed documents are just there, reminders that don’t always remind; the story is tucked away, part of the scenery, and the Torah is simply used – as our other Torah scroll is simply used. Respected, honored, kissed but not often remembered as something unique.

Sometimes, however, an event occurs that brings the story vividly back to our attention. Such an event occurred this past Tuesday night at Temple Emanuel in New York City. The invitation to the event went out by email. There was no other public announcement, and yet there was an astonishing response. Congregants from 75 congregations responded to the call for a gathering of Czech Holocaust Torah scrolls and they came – by car, taxi, bus, plane, train and even on foot – mostly from the tri-state area (NY, NJ and CT), but also from synagogues throughout New England and Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. and Virginia and other states in the southeast. The furthest scroll was brought from Washington State. Naomi and I were there representing two congregations. We brought the Torah scroll from D’vur Kralove which has been in the possession of our New Jersey congregation since 1975, and we brought a short printed history of the Torah scroll in our ark here at Temple Beth Shalom, scroll #720, and a copy of WE ADOPT AS OUR OWN THE DESTROYED JEWISH COMMUNITY OF JIHLAVA, the 134 page monograph about Jihlava and our own Holocaust losses that our congregation published in 2010.

Sometimes, however, an event occurs that brings the story vividly back to our attention. Such an event occurred this past Tuesday night at Temple Emanuel in New York City. The invitation to the event went out by email. There was no other public announcement, and yet there was an astonishing response. Congregants from 75 congregations responded to the call for a gathering of Czech Holocaust Torah scrolls and they came – by car, taxi, bus, plane, train and even on foot – mostly from the tri-state area (NY, NJ and CT), but also from synagogues throughout New England and Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C. and Virginia and other states in the southeast. The furthest scroll was brought from Washington State. Naomi and I were there representing two congregations. We brought the Torah scroll from D’vur Kralove which has been in the possession of our New Jersey congregation since 1975, and we brought a short printed history of the Torah scroll in our ark here at Temple Beth Shalom, scroll #720, and a copy of WE ADOPT AS OUR OWN THE DESTROYED JEWISH COMMUNITY OF JIHLAVA, the 134 page monograph about Jihlava and our own Holocaust losses that our congregation published in 2010.

Now, from 1964, when the Memorial Scrolls Trust started distributing the scrolls to congregations around the world, until 1969, when Communism collapsed, Cold War fears kept these congregations with Czech scrolls from knowing anything about their scrolls except the name of the town from which the scroll had come. No information about the Jews who had been deported. None of their names, their ages, their stories, or where they were murdered. Nor did we know if scrolls from the same Czech congregation were in the possession of other synagogues in the West.

Now, from 1964, when the Memorial Scrolls Trust started distributing the scrolls to congregations around the world, until 1969, when Communism collapsed, Cold War fears kept these congregations with Czech scrolls from knowing anything about their scrolls except the name of the town from which the scroll had come. No information about the Jews who had been deported. None of their names, their ages, their stories, or where they were murdered. Nor did we know if scrolls from the same Czech congregation were in the possession of other synagogues in the West.

Since then, it has all changed. And this event, with a procession of 75 scrolls witnessed by more than 800 people, was a brilliant and moving affirmation of Jewish memory.

Since then, it has all changed. And this event, with a procession of 75 scrolls witnessed by more than 800 people, was a brilliant and moving affirmation of Jewish memory.

Temple Emanuel is one of the largest synagogues in the world. The gathering took place in their main social hall, a large rectangular room with raised balconies along both sides of the enormous space. Along the balcony on the far side were two rows of huge, rectangular tables on which the scrolls were placed. Beside each scroll was a placard identifying it by its Memorial Scrolls Trust number, the Czech town from which the scroll had originated, and the name of the congregation that holds the scroll in permanent trust.

As participating congregations came in with their scrolls, the excitement as tangible – and mounted. People immediately started telling each other their stories – where their scroll came from, how their congregation learned about the Trust, how the scroll came into their possession, if their scroll was kosher or so defiled that it could not be used but only put on display, what they have been doing over the years to honor their scroll and the memory of the Jewish community of which in many cases the scroll is the only survivor. People compared the mantle designs and described the crowns and pointers (which they had not brought with them, per the instructions of the gathering’s organizers).

As participating congregations came in with their scrolls, the excitement as tangible – and mounted. People immediately started telling each other their stories – where their scroll came from, how their congregation learned about the Trust, how the scroll came into their possession, if their scroll was kosher or so defiled that it could not be used but only put on display, what they have been doing over the years to honor their scroll and the memory of the Jewish community of which in many cases the scroll is the only survivor. People compared the mantle designs and described the crowns and pointers (which they had not brought with them, per the instructions of the gathering’s organizers).

The main feature of the event was a solemn procession of scrolls down the center aisle of the room to the stage while the entire assembly stood and a violinist played variations on Hatikvah. Three rows of Torah scrolls were displayed. Some 800 people, many photographing and almost everyone with tears in their eyes.

The main feature of the event was a solemn procession of scrolls down the center aisle of the room to the stage while the entire assembly stood and a violinist played variations on Hatikvah. Three rows of Torah scrolls were displayed. Some 800 people, many photographing and almost everyone with tears in their eyes.

The event was certainly very sad, but it was also exhilarating.

Our congregation’s custom is to read six names each week in our kaddish list. So the 131 names are each read about twice a year, and all the names are read aloud on Yom Kippur and included in our Book of Memory. These names are our tangible connection to the six million and all the martyrs of our people. With their names, the Holocaust story becomes very specific and unforgettable – four year old Jiri Hermann; 5-year old Eva Singerova; or 98 year old Anna Weinerova – all enemies of Hitler’s Reich. I am extraordinarily moved when members of the congregation rise to honor the names and memory of people we never knew personally but who have become ours, part of our Jewish awareness that we choose to include as we shape our conscience and consciousness.

In this week’s parashah, Terumah, Moses calls upon the Israelites to make contributions to build the tabernacle. The verse invites kol ish asher yid’venu libo — every person whose heart is willing (Exodus/Shmot 25:2) – to make contributions. When we read the names of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Jihlava we are performing a service of the heart. And that is one important way the verse that follows in the Torah portion – v’asu li mikdash v’shakhanti b’tokham – let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell in their midst (Shmot/Exodus 25:8) – is fulfilled. That verse is on the wall of this sanctuary. But it is the devotion of willing hearts that makes our congregation, at its best, a place and a people holy to God.

In this week’s parashah, Terumah, Moses calls upon the Israelites to make contributions to build the tabernacle. The verse invites kol ish asher yid’venu libo — every person whose heart is willing (Exodus/Shmot 25:2) – to make contributions. When we read the names of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust from Jihlava we are performing a service of the heart. And that is one important way the verse that follows in the Torah portion – v’asu li mikdash v’shakhanti b’tokham – let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell in their midst (Shmot/Exodus 25:8) – is fulfilled. That verse is on the wall of this sanctuary. But it is the devotion of willing hearts that makes our congregation, at its best, a place and a people holy to God.